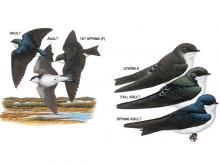

Nonstick Chemicals May Be Affecting Tree Swallows Along Mississippi River

A new U.S. Geological Study report suggests that chemicals found in nonstick cookware and water repellents could be affecting tree swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) living along the upper Mississippi River. It's been known that the Mississippi River around and south of the Twin Cities is contaminated with perfluoroalkoxy (PFA), a chemical found in many household products. The report says wastewater discharges and contaminated groundwater from manufacturer 3M's facilities have created hotspots for PFAs, even though it's been more than a decade since the company stopped producing them. USGS researchers studying tree swallows in Wisconsin and Minnesota found that birds with high concentrations of PFAs are less likely to hatch.