Frogs, toads and salamanders often fall through the cracks of scientific study, but according to recently published research from Montana State University, they play a role so important they should be incorporated into strategies for conserving freshwater fisheries. In his first peer-reviewed paper as sole author, Niall Clancy, 22, said that native fish populations continue to decline around the world despite advances in management practices. Therefore, fisheries managers might want to add new approaches to the old. Clancy is a 2017 graduate from the Department of Ecology in MSU’s College of Letters and Science. His paper, “Can Amphibians Help Conserve Native Fishes?” was published in Fisheries, a monthly journal of the American Fisheries Society, the oldest and largest professional society representing fisheries scientists.

“A complementary suite of techniques and approaches is needed if management is to prevent further losses,” Clancy said. “One such complementary approach is the preservation of organisms that maintain ecosystem processes and functions.” Amphibians — those cold blooded creatures that need both land and water to complete their lifecycles — are such organisms, Clancy said.

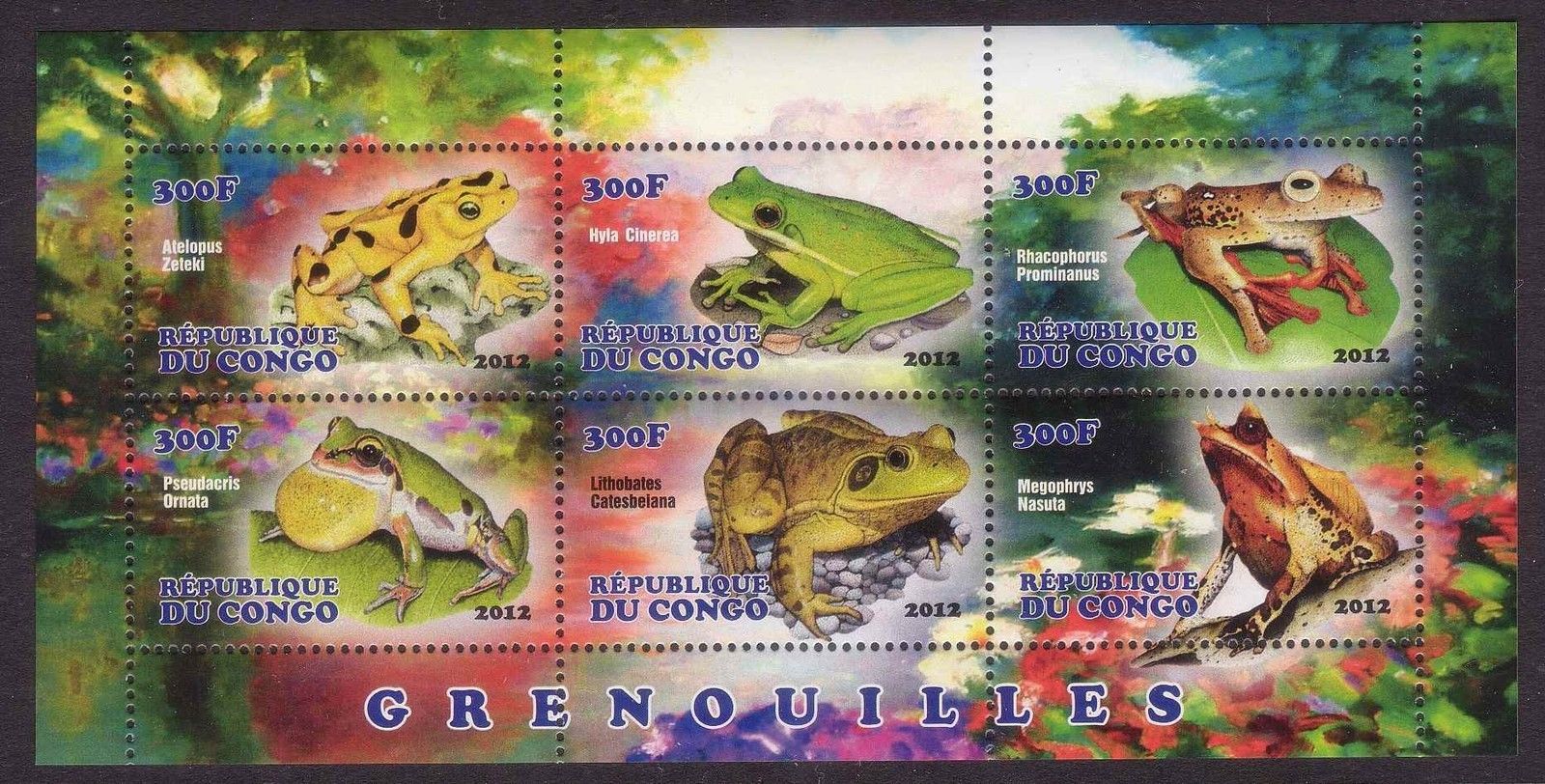

Wildlife biologists tend to overlook amphibians because they aren’t fully terrestrial, Clancy said. Fisheries experts do the same because amphibians aren’t fully aquatic. But in many flowing and standing waters, young frogs, toads and salamanders are the dominant vertebrates. They change water chemistry, redistribute nutrients and alter the habitat for fish and other aquatic organisms.

Clancy noted the amphibians in his study can be both predator and prey. Bullfrogs eat young fish and fish eggs, for example. Fish eat tadpoles. Salamanders tend to be carnivores, while tadpoles are generally herbivores. Both affect their environment, but in different ways. The actions of freshwater fisheries managers would be most effective where amphibian populations abound, Clancy said. To preserve or boost those populations, he suggested that managers remove invasive fish from lakes and streams and stop stocking hatchery fish in lakes that don’t normally contain fish. Additionally, they could record the types and numbers of amphibians they encounter while conducting fieldwork.

When land is involved, fisheries managers might take on an advisory role, Clancy said. They could suggest limiting human activity where amphibians live in large numbers. They might encourage riparian buffer zones, the reduction of pesticide application near water, and maintaining or improving microhabitats that are important to amphibians. Among those microhabitats are rotting logs, leaves, dense tree stands and wetlands.

“Fisheries management plans that incorporate amphibians will likely be beneficial for much of the aquatic community,” Clancy said. His paper focused on two categories of amphibians — one being toads and frogs and the other being salamanders. A third group, called Caecilians, is not found in North America, Clancy said. Caecilians are wormlike amphibians that live mostly underground in the wet tropical regions of South and Central America, Africa and southern Asia.

Source: Sidney Herald, Sept 26, 2017

http://www.sidneyherald.com/news/researcher-touts-potential-of-frogs-to…

- Login om te reageren