In a desperate bid to save a nearly extinct species, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced Thursday that it is launching a captive breeding program for Florida's grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum floridanus). If they do nothing, experts predict the sparrow will go extinct in three to five years, just like its cousin, the dusky seaside sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus nigrescens). The dusky disappeared from the Earth in 1987 when the last survivor died at Disney World. If the Florida grasshopper sparrow vanishes, it would be the first bird species to go extinct in the United States since then, according to the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology."Captive breeding is labor intensive and challenging. It is generally done as a last resort and there are no guarantees. But we have to try," said Larry Williams, the head of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service office in Vero Beach. "This is an emergency and the situation for this species is dire. This is literally a race against time." Biologists estimate that fewer than 200 of the tiny birds remain. State and federal biologists plan to spend the next three months hunting for sparrow eggs, hoping to collect up to 20 to take to the Rare Species Conservatory Foundation in Loxahatchee. The eggs would be placed in incubators until they hatch.

Biologists hope any hatchlings will emerge in 11 to 13 days. They will receive round-the-clock care in hopes they will grow up and breed further in captivity. The cost of starting the program, estimated at $68,000, is being covered by grants, said Ken Warren, a spokesman for the Fish and Wildlife Service.

The ultimate goal is to release some back into the wild, perhaps in two to three years, Williams said. But biologist Paul R. Reillo, president of the Rare Species Conservatory Foundation, said getting captive-raised birds ready for release could take a long time.

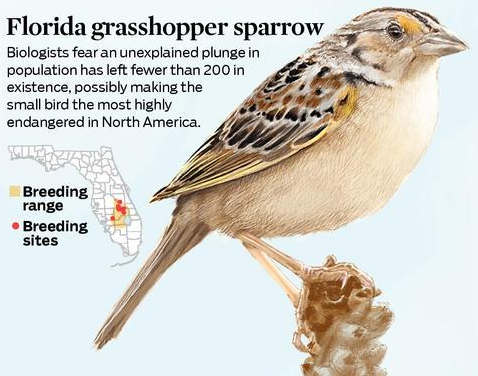

Florida grasshopper sparrows are about 5 inches long, with flat heads, short tails and black and gray feathers that help them hide their nests amid the low shrubs and saw palmetto of the state's grassy prairies.

They are generally heard more than seen, with a call that consists of two or three weak notes followed by an insectlike buzz —- hence their name. Biologists hope to follow the sound of their songs to track down their nests.

"We know it's going to be hard," Williams said. "They're small birds living in dense vegetation and they're secretive by nature."

The bird was first described in 1902 by U.S. Army surgeon Maj. Edgar A. Mearns, when their population was widespread across south-central Florida. By the 1970s, so many of the prairies that form their habitat had been ditched and drained and converted to pastures or sod production that the sparrow population plummeted.

They were added to the federal endangered species list in 1986, when an estimated 1,000 remained on public preserves at the Three Lakes Wildlife Management Area in Osceola County, the Avon Park Air Force Range in Highlands and Polk counties and the Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park in Okeechobee County.

In the past decade, Williams said, state and federal biologists have worked hard to restore lost habitat and to guard against losing any. Yet the most recent bird counts found the population now remains only in Osceola and Okeechobee counties, and may number fewer than 200. So far, no one knows why.

Captive breeding is a last-ditch effort to save a species. There are some major success stories, such as with whooping cranes and California condors, Warren said.

But using captive breeding to save the dusky seaside sparrow failed because officials started it too late. They found only males in the wild.

More recently, a captive breeding project to save the endangered Key Largo wood rat failed because the captive-bred rats did not know how to avoid predators in the wild and wound up being eaten. One, wearing a small radio-collar for tracking, was swallowed by a python, the first to be found in the Keys.

Still, federal officials said they had no choice but to give captive breeding a try and hope it works.

"We're trying to prevent a unique part of Florida's landscape from vanishing," Williams said.

Meanwhile, he said, they're also keeping an eye on another one of the dusky sparrow's cousins that's on the endangered list, the Cape Sable seaside sparrow (Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis). There were 6,000 living in the Everglades in 1992, but by 2009 the number had dropped to 3,000.

Source: Tampa Bay Times, 12 November 2014

http://www.tampabay.com/blogs/state/the-plight-of-the-florida-grasshopp…

- Login om te reageren