Sacramento’s remnant population of the Purple Martin Progne subis, a swallow recognized as a state Species of Special Concern, declined again in 2008 according to a recent survey. The number of nesting martins declined to 84 nesting pairs, a 21% decline from last year. The population is at the lowest level recorded since surveys were initiated in the early 1990s. The continued population decline in Sacramento worries biologist Dan Airola, who has been studying and managing the purple martin population for years with a group of dedicated volunteers. “Over the last 4 years, the population has decreased by over 50%, which is pretty dramatic” Airola notes.

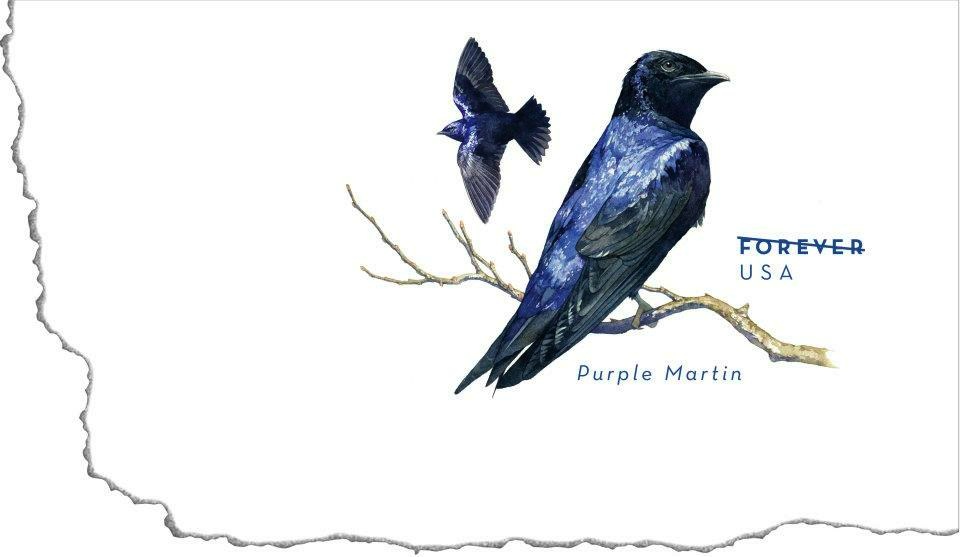

The martin, the largest swallow species in North America, was once common in the Central Valley. It was eliminated from nearly the entire Valley in the 1970s, following the arrival of the non-native European Starling, a nest-site competitor.

In Sacramento, martins survived by learning to nest within longer overpasses and elevated freeways, which they enter through “weep holes” on the undersides of the structures. Use of these bridges apparently minimizes competition for nest sites with starlings. The most likely cause for decline this year is drought, and its effects on the insect food supply for the martins. Martins are “aerial insectivores” capturing larger insects while soaring above the city and adjacent farmland. “When rainfall is low, aerial insect populations decline”, says Airola.

“Although most animals typically recover from drought conditions, the current low population now increases risk of further decline due to other causes” notes Airola. “Also, we don’t know whether this decline is indicating potential long-term effects of climate change, or if it was just a bad year”, he says. “But”, he emphasizes, “it’s pretty clear that any change in climate that creates drier spring conditions would be detrimental to the martins”.

Other threats to martins include the wave of recent in-fill development and transportation improvements, which can eliminate key habitat conditions for martins. Currently, projects with possible habitat conflicts are proposed at sites that support over 60% of the remaining nesting population, according to a recent study published by Airola and colleagues.

Redevelopment projects, including the Downtown and Curtis Park Railyards projects, can eliminate critical areas that martins use for perching and collecting nesting material. They also may increase traffic and resulting collision mortalities. The projects also may change the urban habitat in ways that increases starling populations and the resulting nest site competition.

This year, with partial funding from Sacramento Audubon Society, the volunteers have addressed effects of these projects. “It’s been an uphill struggle to get approving agencies to pay attention to the needs of Purple Martins, but I think we got their attention this year”, notes Airola. “Right now, everyone’s being pretty cooperative”.

Martins have a high tolerance for human activity, which explains their persistence to date in highly urbanized areas.

Airola also studied the martins’ response to construction of a parking lot beneath their nesting bridge at one site this year. Despite frequent disturbance, the bird remained at the site and bred successfully. “Honestly, I was surprised that they would tolerate the high level of noise and activity”, says Airola. “It tells us that the martins can be maintained in busy urban areas, as long as their habitat needs are met”.

The biologists, however, are not relying solely on bridges to maintain the remnant martin population. This year Airola and colleagues erected specially-designed martin nest boxes at the California Department of Fish and Game’s Yolo Bypass Wildlife area. There, they play martin songs to attract martins to nest. So far, no martins have adopted the boxes.

“Transitioning Purple Martins to nest boxes requires long-term commitment” notes volunteer Stan Kostka, who manages box colonies in Washington’s Puget Sound, and drives annually to Sacramento to help conduct martin research and management. “We’ve used boxes to recover populations elsewhere, so we are hopeful we can do it here” , Kostka notes.

“The key”, Airola emphasizes, “is to protect the Sacramento bridge-nesting birds, to provide new breeding birds to colonize the boxes and other bridges in the Valley. This colonization would contribute to the ultimate recovery of the species. “We were just lucky that we didn’t lose the species entirely before to the previous starling invasion”, he notes. “If we lose these Sacramento birds now, we pretty much lose the opportunity to recover the species to its former range within the entire Central Valley. But we’re pretty determined to not let that happen.”

Source: Sacramento Audubon Society

http://www.sacramentoaudubon.org/purplemartins.html

Bird List (English-Dutch):

http://members.ziggo.nl/devalk/vogellijst.htm

The Purple Martin (Progne subis) is the largest North American swallow. These aerial acrobats have speed and agility in flight, and when approaching their housing, will dive from the sky at great speeds with their wings tucked. Wintering in South America, purple martins migrate to North America in spring to breed. Their breeding habitat is open areas across eastern North America, and also some locations on the west coast from British Columbia to Mexico. Purple Martins are aerial insectivores, meaning that they catch insects from the air. The birds are agile hunters and eat a variety of winged insects. Rarely, they will come to the ground to eat insects. They usually fly relatively high, so, contrary to popular opinion, mosquitos do not form a large part of their diet.

Source: Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Purple_Martin

- Log in to post comments